The revival of Silk Road

The Belt and Road Initiative, BRI in short, reflects China’s vision to revive the ancient trading routes that connect the East with the West. The Modern Silk Road represents the largest market worldwide that accounts for 3 billion people and extends beyond the three continents of Asia, Africa, and Europe.

The idea was born for the first time in 2013 when the Chinese President visited Kazakhstan. The goal was to highlight the crucial role of Central Asia in the regional economy; a year later, the Chinese national agenda incorporated the Silk Road initiative. The section below aims to explore further this initiative by breaking down its core elements.

Re-introducing the Silk Road

The Belt and Road Initiative consists of three axes:

- The belt refers to overland corridors linking China with Central & South Asia and Europe.

- The road corresponds to the maritime shipping routes that connect China with Southeast Asia, the Gulf countries, North Africa, and Europe.

- The six Corridors that connect more countries to the BRI: Mongolia and Russia; Eurasia; Central and West Asia; Pakistan; Indian sub-continent; Indochina.

In reality, the BRI is an upgrade to the old Marco Polo route, which extends from old sea lanes to include land transport. Hence, the BRI initiative encompasses a mix of ports, bridges, fuelling stations and industrial infrastructure.

Although the primary focus of the plan is the trade and infrastructure funding, it also expands in other areas that could profit global economy:

- the digital aspect of commerce;

- the tax cooperation and a plan to establish international commercial courts to settle international disputes;

- infrastructure interconnectivity in the transport and energy sector under the six economic corridors;

An area that has received lots of criticism is the funding model of the BRI. The next segment examines the structure of the BRI financing model, which will help the reader understand the real motive behind China’s financial aid.

The BRI funding model

The estimated cost of the BRI is said to overcome the $1tn. Because BRI’s financial model originates from Chinese state funds, the initiative is also known as the Chinese Marshall Plan.

To a lesser extent, funding stems from Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) led by China. The heart of the multilateral funding originates from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which is responsible for financing various Asian projects. Another source of capital is the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, which provides financial aid for its member-states.

The dynamic of the BRI is impressive, as it is estimated to cross 71 countries. Kuo and Kommenda note that the initiative represents half of the global population and a quarter of the world GDP.

Now that it is evident how the financial support works under the BRI, it is time to dig further into China’s real motive of reviving the old Silk Road.

The real motive behind the BRI

In the modern multi-polarised world, China has emerged as a global power with a growing economic and political weight on world affairs; the shift from introversion to extroversion projects the desire to become a leading Asian power that strives for growth and holds global aspirations. To unravel the driving force behind China’s Belt and Road Initiative, one should look into its domestic and regional politics.

In domestic affairs, China faces the constant fear of socio-economic turbulence. The underlying economic disparity between its South and West could unleash forces of terrorism and separatism; a potential coalition would pose an imminent threat to the Chinese territorial integrity.

At the regional level, the instability of many Asian political regimes could have a spillover in the most deprived areas of China; surrounded by land, the country borders with 15 other states, with some suffering from unstable regimes and others seeking partners.

Based on these two parameters, it is evident that China’s plan for economic development and cooperation is motivated by security needs; as Chatham puts it: “belt and road investments are viewed as a way to facilitate China’s periphery diplomacy” (Jie and Wallace, 2021). In other words, China is in immediate need to expand its economy outside its borders and boost its international trade in the hope that it will profit its businesses also abroad.

For all these reasons, the principle of the BRI partnership is the mutual economic benefit both for the participating states and China; successful partnerships already include energy-exporting countries from Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan), as well as ASEAN states, located close to China, and of high importance for its security.

Consequently, the BRI falls under China’s global agenda for global security and economic growth. The question is: to what extent this initiative can be deemed successful? And, what are the constraints for delivering its objectives? The following section aims to address these points.

What the future holds

As discussed, the primary focus of BRI is trade cooperation and infrastructure funding but is not limited there; it extends to other areas such as policy, cultural exchange, and people-to-people connectivity.

The two areas below aim to unravel the opportunities and constraints that lie ahead.

- Opportunities:

The BRI model seeks to diffuse Chinese standards into the participating countries. As the global economy shifts from heavy industry and construction, the BRI will need to switch to more sophisticated, high-end technologies such as aerospace, robotics, low carbon technologies, electric power, and next-generation IT.

By doing so, both China and its partners will reap the gains of the new Silk Road; if this project proves successful, it could boost the regional economies and bring prosperity to low-income countries. In addition, interconnectivity among the BRI countries could rocket cross-border trade by cutting down the shipping time and improving the BRI growth, as Ruta suggests.

For China, the exportation of high-technology standards to the BRI economies equals future buyers of Chinese products. Indeed, data shows that Chinese exports have increased from 19% in 2000 to 34% in 2016 towards the BRI economies. This trend proves that the BRI trade grew significantly and could further progress in the region.

Towards this direction, China is already competing with the other global powers over technological innovation. A leader in telecommunications, Huawei, the largest mobile phone producer globally, is pioneering in 5G technology.

Green energy is another industry where China has taken the lead. China’s achievements correspond to advanced technology for clean energy, mitigation of carbon emissions and access to a transcontinental power grid between China, Japan, Mongolia, Russia, and Korea.

- Constraints

Despite the positive developments, there are some hurdles towards meeting the BRI goals. First of all, the amount of capital that China has distributed to many BRI economies will soon put a brake on the capital flow. Likewise, OECD anticipates that the Chinese funds will run into constraints at home.

Secondly, the distribution of loans to non-performing projects entails the risk of capital loss. OECD has already warned China for funding 43 economies with low credit ratings. Due to their weak economies and other domestic problems, underperforming countries might fall into debt and may not be able to repay their loan. For this reason, international organisations have called for coordinated aid to support the BRI countries improve their investment environments and infrastructure.

Another concern raised is the quality of the final BRI projects. In some cases, there have been reports of safety compromise and environmental violations with the delivery of the final project compared to similar projects of other advanced economies.

Last but not least, it is crucial to address the conflicting interests between China and other global powers, which could spark world disputes. For the United States, the emphasis on free access in the international sea lanes overlaps with the Chinese interests. As for Russia, its plans collide with China’s new agenda in Central Asia; for Moscow, the region includes states of the former Soviet Union, which considers as part of its influence sphere.

Conclusions

Closing, the Belt and Road Initiative presents both positive and negative points for the future of the regional and global economy. It is yet to see how the world will react to this initiative and how China will adapt to the new challenges that emerged from the pandemic. These two questions will be the topic of the article “Redefining the Belt and Road Initiative in a Post-Pandemic World“.

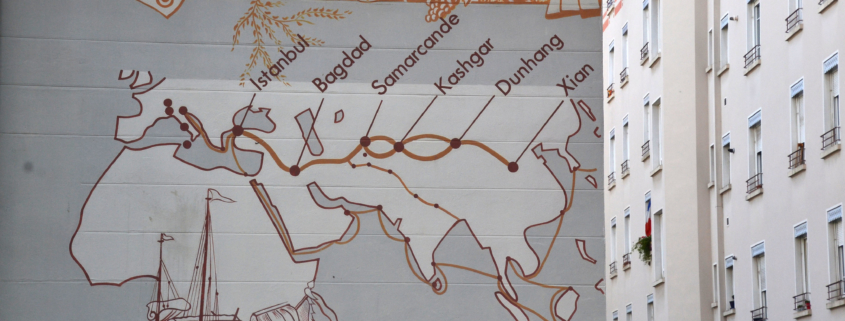

Photo: Jeanne Menjoulet. Silk Road: A mural made in the 1960s (2019). Source: (flickr.com)| (CC BY 2.0)

Bibliography

Aaltola, M., & Käpylä, J. (2016) U.S. and Chinese Silk Road Initiatives: Towards a Geopolitics of Flows in Central Asia and Beyond, In H. Rytövuori-Apunen (Ed.), The Regional Security Puzzle around Afghanistan: Bordering Practices in Central Asia and Beyond, Barbara Budrich, Opladen and Toronto: 207–242, Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvbkjzm0.14 [Accessed 30/01/2022]

De Soyres François (2018) The Growth and Welfare Effects of the Belt and Road Initiative on East Asia Pacific Countries, Number 4, World Bank Group, Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/896581540306960489/pdf/131211-Bri-MTI-Practice-Note-4.pdf [Accessed 27/01/2022]

Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Sweden (2019) The Belt and Road Initiative Progress, Contributions and Prospects, 2019.4.22, Office of the Leading Group for Promoting the Belt and Road Initiative, Stockholm, Available at: https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/cese/eng/zgxw/t1675676.htm [Accessed 27/01/2022]

Gyu L. D. (2021) The Belt and Road Initiative after COVID: The Rise of Health and Digital Silk Roads, Asan Institute for Policy Studies, Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep29688 [Accessed 28/01/2022]

Jie Y and Wallace J. (2021) What is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)? Chatham House, Available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/09/what-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-bri [Accessed 26/01/2022]

Kuo Lily and Kommenda N. (2018) What is China’s Belt and Road Initiative, The Guardian, 30th of July, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/ng-interactive/2018/jul/30/what-china-belt-road-initiative-silk-road-explainer [Accessed 26/01/2022]

Luft G. (2017) Silk Road 2.0: US Strategy toward China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Executive Summary, Atlantic Council, Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep16785.4 [Accessed 29/01/2022]

Mobley T. (2019) The Belt and Road Initiative, Strategic Studies Quarterly, 13 (3): 52-72, Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26760128 [Accessed 29/01/2022]

OECD (2018) China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape, OECD Business and Finance Outlook 2018, Available at: https://www.oecd.org/finance/Chinas-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-in-the-global-trade-investment-and-finance-landscape.pdf [Accessed 28/01/2022]

Peel M. and Fleming S. (2021) West and allies relaunch push for own version of China’s Belt and Road, The Financial Times, May, Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/2c1bce54-aa76-455b-9b1e-c48ad519bf27 [Accessed 27/10/2022]

Ruta M. (2018) Three Opportunities and Three Risks of the Belt and Road Initiative, World Bank Blogs, 4th of May, Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/trade/three-opportunities-and-three-risks-belt-and-road-initiative [Accessed 27/01/2022]

Sutter K., Schwarzenberg A. and Sutherland M. (2021) China’s “One Belt, One Road” Initiative: Economic Issues, IF11735, Version 2, Congressional Research Service, 22th of January, Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11735(Accessed 27/01/2022)

The State Council The People’s Republic of China (2021) China’s International Development Cooperation in the New Era, White Paper, The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 10th of January, Available at: http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/202101/10/content_WS5ffa6bbbc6d0f72576943922.html [Accessed 27/01/2022]

176th Wing Alaska Air National Guard's photostream

176th Wing Alaska Air National Guard's photostream

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!